What if the most enduring form of guidance wasn’t given through books and speeches, but through the quiet act of collecting wood with someone who sees your soul?

Henry David Thoreau’s Letters to a Spiritual Seeker echoes a spirit reminiscent of Ghazali’s Ayyuhal Walad, but what it offers is more intimate: not a treatise, but a detailing of a lived companionship between seeker and guide.

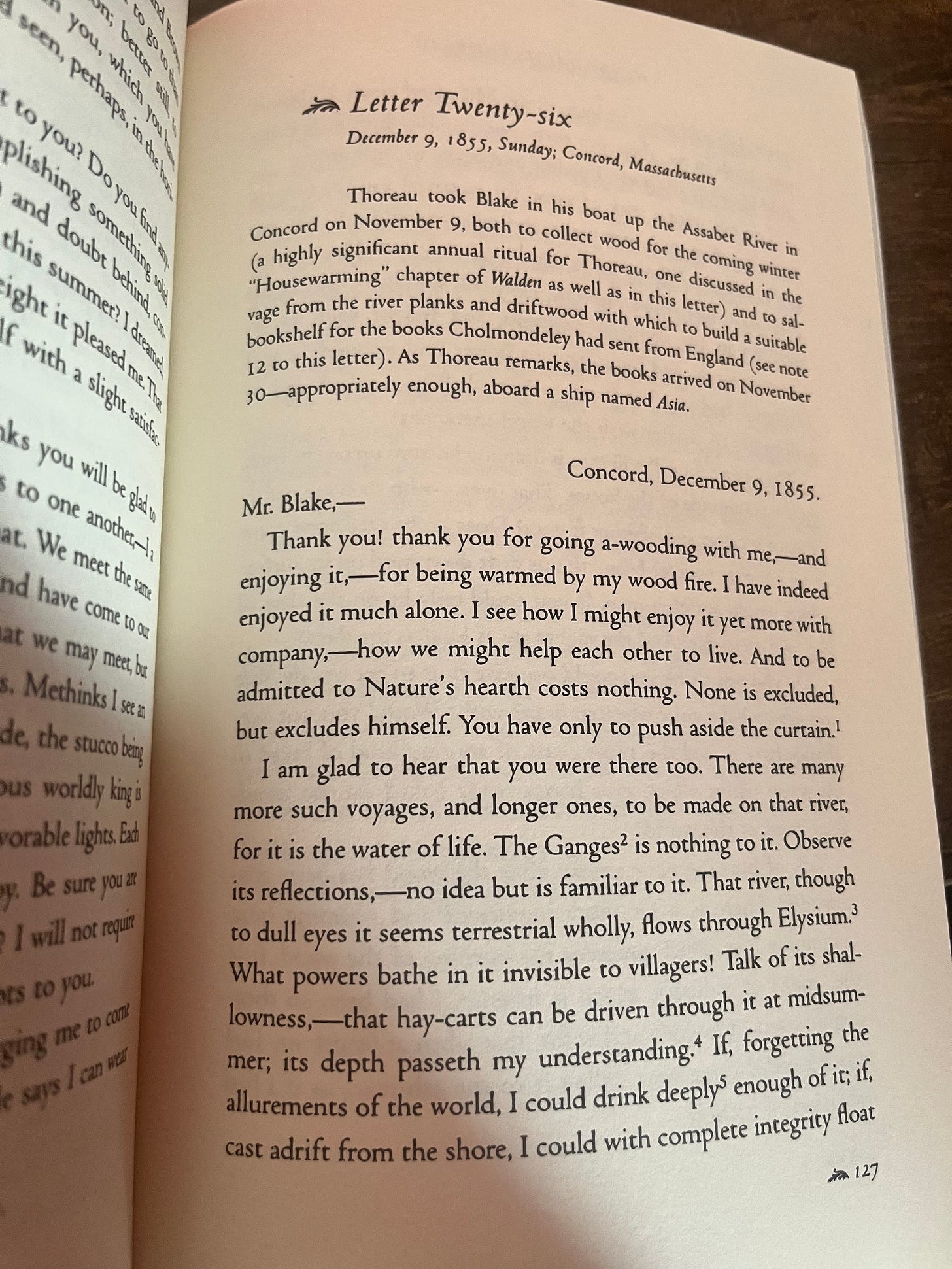

Thoreau—spiritual philosopher, naturalist, and one of the great American minds of the 19th century—writes to Harrison Blake not as a distant guide, but as a fellow traveler. In this letter, he invites him on a nature trip. It was primarily to gather wood. While the reason seems mundane, what emerges is a subtle and sacred truth and offers a profound entry into a more holistic understanding of companionship and the spiritual task of living together:

“I see how I have enjoyed it much alone.

I see how I might enjoy it yet more with company—how we might help each other live.”

The most important lesson here is Thoreau’s definition of true friendship and mentorship, which are not always distinct: “how we might help each other live.”

The interdependence we all share and require for a meaningful life was an inherent understanding since the beginning of humankind. Even those who enjoy their own company the most recognize a deficiency uncured without deep connections. If this weren’t the case, loneliness wouldn’t be an epidemic and one of the biggest agents in much of the mental health crisis.

Even the most secluded seeker needs someone to walk beside him.

Three truths I returned to while reading this letter:

Mentorship is an embodied and practical transmission.

Mentorship shouldn’t just be about giving theoretical (and general) advice to someone in need. As important as that is, something else is also required. There’s a living together, as Thoreau mentions above, where lessons are taught in real-time. Guidance, at its most transformative, does not remain in theory. Unfortunately, how many of our efforts to guide people in community are completely divorced of giving them life skills and simply showing them how to live?

Thoreau articulates something that the Islamic spiritual tradition referred to as mulāzamah—a companionship through which knowledge is not just taught, but absorbed through presence, humility, and shared time. It moves into shared meals, walks, sitting side by side in nature or prayer and service of one another. It’s not only about what is said, but what is transmitted in silence. No less important was suhbah with others on the path including those you felt had nothing to offer you (More on this in the future inshallah).

Related to this is the thoughtfullness required for real mentorship and friendship. I am amazed at how many scholars of our tradition penned entire treatises and books in response to just one query or concern from a sincere seeker. Thoreau in this work doesn’t miss an opportunity to ask thoughtful reflections about Blake,

True mentorship is reciprocal.

There’s an acknowledgement of true mentorship being two-sided. While hierarchy is important for knowledge transmission and spiritual development, the greatest mentors know they are benefitting just as much from their mentees, at times more. I’ve witnessed this in my own teachers, who often admit they are refined through the questions, presence, and sincerity of those they are teaching and guiding.

The best seekers never arrive thinking they’ve come empty-handed—but they do arrive empty of ego, ready to be filled with whatever the journey gives them. This never stops being true, even when you are tested with the responsibility of guiding others.

Wisdom transcends age and title.

Interestingly, Thoreau and Blake (the seeker) were the same age. Blake had the humility to recognize his peer was far more actualized and sought out his company. Thoreau felt the same and they both benefited. In my own personal life, I’ve found some of the most significant mentorship in my own life has come from peers and colleagues. Yet how many are blinded by pride and jealousy, blocking benefit from those most able to help them?

Wisdom is the lost property of the believer.

Wherever they find it, they have a greater right to it. -Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

We live in a world that demands we outperform, outshine, and outpace one another. Capitalism, by design, thrives on competition—and while some forms of competition are healthy (as I’ve written about before), this structure often breeds jealousy and incentivizes the climb over others in pursuit of our own goals.

But when we internalize that logic, we forget something essential: the purpose was never to ascend alone, collecting accolades over the graves of our peers—but to rise by elevating one another

What is lost is the joy and art of Thoreau’s line which lingers throughout the letter and book: “how we might help each other live.” It is perhaps the simplest—and most sacred—definition of friendship, mentorship, and even love.

We were never meant to become more human by ourselves.

May God grant us companions, mentors and guides who remind us how to live, not just in comfort, but especially in the quiet, hidden and difficult moments where most growth happens; and through whose company even the most painful moments of our journey become beautiful.

Dua Request

This write-up was special as the book was gifted to me 10 years ago by a dear friend Obada Ghabra. He wrote me a beautiful note in the book which reflected the lessons I hoped to elucidate through these small reflections. Please pray for him and his family.

And normalize gifting each other books, but not without a personalized note. 10 years later, and I am still touched by it.

Let me know if you liked this small write-up and if you want more.